By Uzma Gilani, Lecturer in Health and Social Care Management, FSB Digbeth

“Students do not care how much you know

until they know how much you care.”

— John C. Maxwell

How many students must quietly unravel before we take notice?

Each academic year, behind the metrics and module grades, there are learners who silently slip through the cracks—struggling with anxiety, isolation, financial pressure, or personal loss. They disappear not with dramatic exits, but with missed lectures, delayed submissions, and fading confidence.

Yet too often, pastoral care is triggered only when a student is already in crisis. We call them in after failures. We offer help when disengagement is already chronic. This is not support—it is damage control.

As educators, we can no longer afford to be passive responders. In an era of rising mental health concerns and widening attainment gaps, pastoral care must become anticipatory, personalised, and deeply embedded in the academic journey.

As a Personal Academic Tutor (PAT) Coordinator, I argue that it is time we fundamentally rethink our approach—shifting from reactive mechanisms to preventive systems built on regular dialogue, intelligent use of student data, and a culture that treats wellbeing as integral to learning, not separate from it.

The Case for Preventive Pastoral Models

Pastoral support in higher education is traditionally seen as student-initiated. However, evidence now strongly suggests that many students, especially those from underrepresented or non-traditional backgrounds, often suffer in silence (Thomas, 2012). The Student Mental Health Crisis has made headlines in recent years, with the Office for Students (2023) reporting rising rates of anxiety, depression, and academic burnout among UK university students.

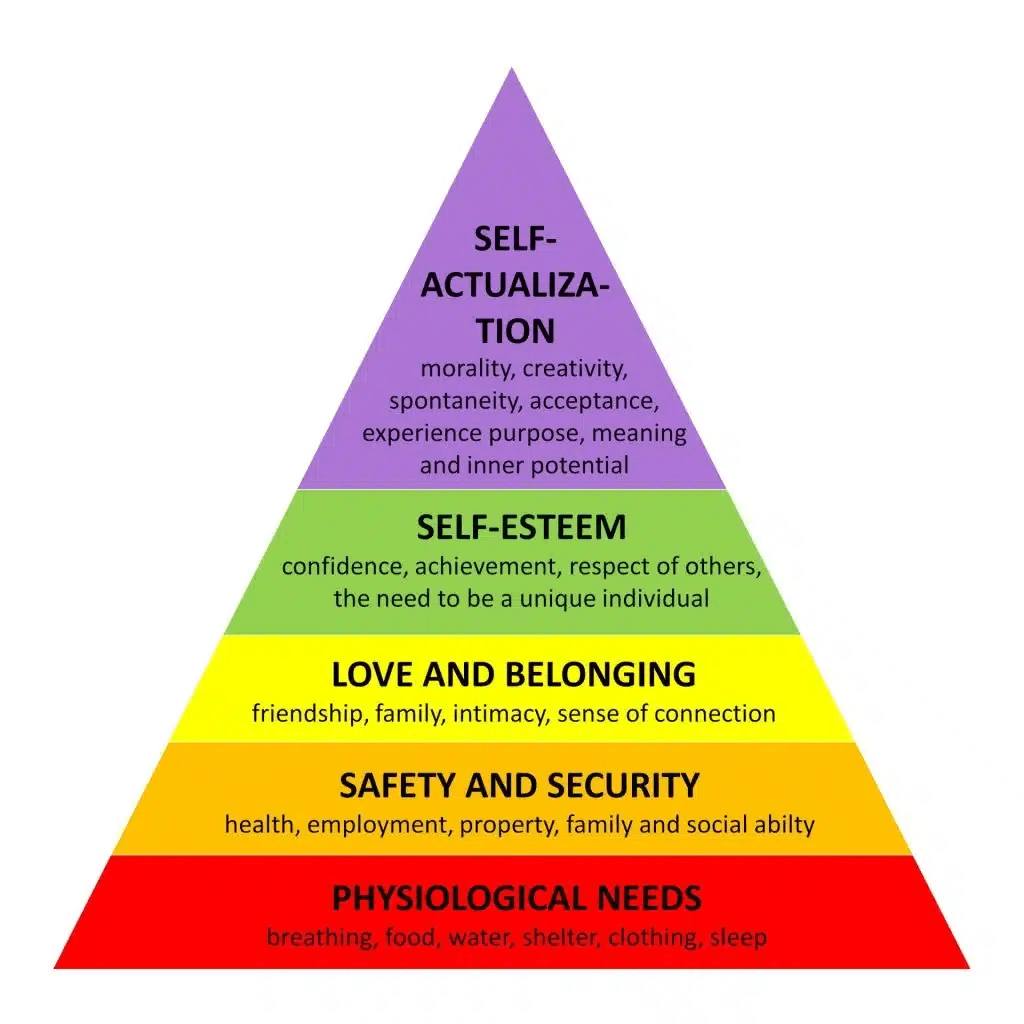

Proactive models of pastoral care are built on early identification and engagement rather than crisis response. They align with the principles of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (1943)— acknowledging that academic achievement is only possible when students feel emotionally safe, socially connected, and psychologically supported.

Using Dialogue and Data to Detect Early Signs

Proactivity begins with two vital tools: dialogue and data.

- Dialogue

Building trusting, ongoing relationships through regular PAT check-ins allows tutors to identify subtle signs of disengagement: poor punctuality, declining confidence, or reluctance to participate. As Carl Rogers’ Humanistic Theory (1951) emphasises, students flourish in environments of empathy, authenticity, and unconditional positive regard.

- Data

Academic analytics—attendance patterns, VLE engagement, formative assessment scores—provide tutors with quantifiable indicators of risk. When used ethically, this data acts as an early warning system, enabling timely interventions before academic decline sets in.

Hattie and Timperley (2007) note that feedback is most effective when it is timely and forward-facing. This reinforces the power of pastoral interactions that are not just reactive, but predictive and preventive.

A Proactive PAT System in Action

At FSB, we recognise that meaningful student support goes far beyond reactive check-ins. Our student demographic is richly diverse—many are first-generation learners, mature students, or international applicants navigating higher education while balancing work, family, or complex personal circumstances. In response, FSB has built a holistic, structured, and preventive pastoral framework that sets an example within the private HE sectors.

Key Initiatives at FSB:

- A Dedicated Personal Academic Tutor (PAT) System

At the heart of our support model is a robust PAT system where every student is assigned a dedicated academic tutor. These relationships are not administrative; they are developmental. Students meet their PATs multiple times throughout the academic year, with sessions designed not only to review academic progress but to discuss wellbeing, career aspirations, and personal challenges. - Early Engagement & Risk Detection

FSB has implemented a centralised dashboard for student engagement tracking. Attendance, punctuality, VLE interaction, and submission patterns are monitored in real-time. When indicators show early signs of disengagement, PATs and support staff intervene promptly. This data-informed approach has been crucial in preventing academic failure and emotional isolation. - Staff Training in Inclusive, Trauma-Informed Support

All staff, including academic tutors, undergo training on how to provide compassionate, non-judgemental, and culturally responsive pastoral care. These sessions incorporate elements of trauma-informed practice, helping staff recognise signs of distress and respond in ways that build trust and resilience. - Embedded Wellbeing Services and Mental Health Referral Pathways

FSB ensures that students have access to internal and external wellbeing and counselling services, with seamless referral pathways. Tutors are trained to make timely and appropriate referrals while continuing to offer consistent academic mentoring. - Community Building through Academic and Social Initiatives

A sense of belonging is one of the most powerful protective factors in a student’s journey (Thomas, 2012; Tinto, 1993). FSB fosters this through academic workshops, peer mentoring schemes, and events celebrating cultural diversity. These initiatives strengthen interpersonal bonds and reduce the stigma often associated with asking for help. - PAT Coordinator Oversight and Quality Assurance

The PAT system is continuously monitored and improved under the leadership of a dedicated PAT Coordinator (my role). Regular tutor debriefs, student feedback surveys, and data reviews ensure that our pastoral approach is both agile and responsive to student needs.

A Call to Action

It is not enough to support students when they stumble. We must walk alongside them from the start. We must be attentive, proactive, and holistic in our approach to student wellbeing—especially within private HE, where students may arrive with unique barriers but also remarkable potential.

Fairfield School of Business has taken critical steps, but the journey continues. As educators, coordinators, and human beings, our challenge is to champion a new standard of care—one where no student slips through the cracks unnoticed.

Let us reframe pastoral support not as a fallback, but as a foundational framework for success.

References

Brooks and Kirk (2023) Understanding Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in Education. Available at: https://brooksandkirk.co.uk/understanding-maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-in-education/ (Accessed: 25 May 2025).

Hattie, J. and Timperley, H. (2007) ‘The power of feedback’, Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp. 81–112.

Maslow, A.H. (1943) ‘A theory of human motivation’, Psychological Review, 50(4), pp. 370–396.

Office for Students (2023) Student mental health in higher education: A review. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk (Accessed: 26 May 2025).

Rogers, C.R. (1951) Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Thomas, L. (2012) Building student engagement and belonging in higher education at a time of change. London: Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

Thomas, L. (2012) Building student engagement and belonging in higher education at a time of change. London: Paul Hamlyn Foundation.