By Miracle Eze, Lecturer in Digital Marketing at FSB Sheffield | Article Date: 07/11/2025

There are times when we are totally oblivious and not even aware of what we are doing online and just scrolling, tapping, liking, or sharing. A light alert or a sound notification, a news story in the corner of our eyes, and we have already clicked unconsciously. Nevertheless, behind that very effortless click lies a sophisticated interaction of chemical reactions in the brain, emotional states, and cognitive bias. Understanding the motives of users to click is not only a matter of curiosity anymore but rather a barometer of digital marketers’ skill in a highly competitive environment. Neuroscience captures those moments of milliseconds when the attention shifts, and the action is taken.

We are going to explore what goes on in our brains while having online interactions with others.

1. Dopamine: The Click’s Reward Circuit

The click brings about a pleasurable feeling as it stimulates the basic motivation and reward system of the brain. Dopamine, the neurotransmitter that plays the most important role in this process, is secreted every time a user clicks a link, reads a message, or receives a “like” on their social media activity (Costa and Schoenbaum, 2022). It signals to you to react since the good outcome “might” happen.

This “might” is of great importance. The unpredictability of rewards is one of the features of variable rewards in social media feeds as identified by Lindström et al., (2021). It is a case of the next post or the next comment creating an expectation that will keep you scrolling even when you are not sure if it will be interesting or not. The mechanism here is similar to that of casinos: the possibility of obtaining something rewarding gets the brain’s same part — the nucleus accumbens — activated, hence every scroll becomes a small bet. Platform designers and marketers employ strategies such as push notifications and endless scrolling to maintain this dopamine release constantly.

2. Attention: The Brain’s Currency

The first and most restricted resource consumed in the digital sphere is attention. The brain of a human being is always on the lookout for the new thing and the most important thing. The reticular activating system (RAS) (Soisoonthorn and Unger, 2025), a part of the brainstem, is responsible for filtering the incoming signals and deciding what is going to be sensed.

In a digital noise-filled world, only the content of emotions or personal experiences get through. The words “urgent,” “free,” or “new” attract the RAS because they are associated with possible gain or loss. Therefore, it can be said that ad headlines and subject lines compete with each other for microseconds of attention. These messages with the strongest power create an atmosphere of emotions or stimulate innate curiosity. For instance:

- “You won’t believe what happened next” arouses curiosity.

- “Limited offer” signals scarcity.

- “People like you are saving money this way” gives social proof.

All the above-mentioned effective messages are dependent upon the neural shortcuts, or heuristics (Hoyos, 2023), that the brain employs for making rapid, low-effort decisions.

3. Emotion: Why We Click First, Think Later

Your limbic system, which controls emotions, is the first to react to the content even before the rational part of your brain has had the opportunity to assess it. The amygdala conveys the emotional relevance in a matter of milliseconds. Thus, information that is emotionally charged — joy, anger, awe, or fear — passes through the Internet faster than any other kind of information. Posts that provoke strong emotions are more likely to be clicked or shared (Abbas et al., 2021; Paletz et al., 2023).

Emotions and decision-making are connected when the obraum texts the strong feelings to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Hence, the statement that we click because it seems right. This turning of events has a significant impact on the marketers’ writing: Emotions attract, but the truths are revealed. Breda (2022) agrees that the brain is prepared to act in response to an attractive web page, emotionally charged pictures, and stories that the viewer can identify with.

4. Cognitive Biases: Mental Shortcuts

Cognitive biases are used by our brains, which are mental shortcuts, to save energy and make the process of decision-making easier. These biases have a significant effect on digital engagement. The online behaviour is mainly characterised by:

- Curiosity gap: We click to end an ideational journey (You won’t believe what…).

- Social proof: Watching others engage (likes, reviews) plays on our very basic social need to conform, which is associated with the release of oxytocin.

- Loss aversion: More than the pleasure of winning, we loathe losing. The neural difference here is taken advantage of by the use of words like “Last chance”.

- Authority bias: The brain tends to trust more what it thinks the experts say, thus stimulating the trust circuits of the prefrontal cortex.

- Visual bias: Imagery is understood by the brain 60,000 times faster than text (Barker, 2024), hence the great images and emojis often have more audience and engagement.

5. The Role of Anticipation and FOMO

Anticipation—a sensation that an enjoyable event is just about to happen—is a major factor that affects clicks. It is like the brain’s mesolimbic dopamine pathway is on fire and it is almost impossible not to act (Li et al., 2015). One way marketers create anticipation is through “Coming soon” teasers or subject lines in emails like “Your exclusive invite is waiting.”

This is amplified by FOMO (Fear of Missing Out). The brain interprets being left out socially as a real danger, which leads to the activation of the anterior cingulate cortex—the area which processes physical discomfort (Chester and Riva, 2016). The use of terms such as “Only 3 spots left” plays on our basic need to belong and to be in-the-know, which is the reason they are so effective.

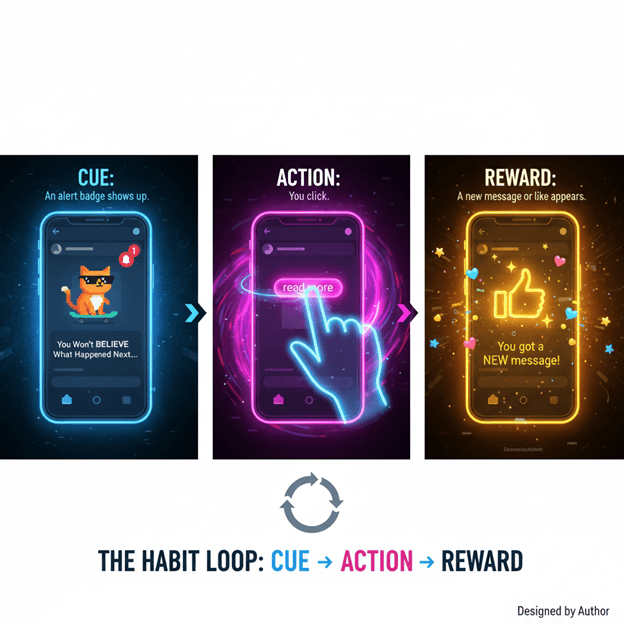

6. The Habit Loop: Rewiring for Repetition

Repeating the same actions leads to the creation of neural pathways, making the corresponding action easier to perform and more automatic. The habit loop gets deeper the more we go online:

For example:

- Cue: A notification icon appears.

- Action: You tap on it.

- Reward: A friend has sent you a message or liked your post.

This cycle becomes automatic in due course. The control is transferred from the part of the brain that deals with self-control and decision making (the prefrontal cortex) to the part that handles routine behaviours (the basal ganglia). Consistent branding and tone are attractive because they allow a brand to be embedded in a user’s mental habit loop, which in turn, increases engagement naturally.

7. Ethical Limits: The Dark Side of Clicks

Manipulation is possible using the same neuroscience that makes marketing successful. Brands run the risk of taking advantage of psychological triggers when they overuse them, especially when it comes to fear, scarcity, or addictive loops.

The reward system may become desensitised after prolonged exposure to these digital dopamine cycles, ultimately reducing motivation and focus (Youvan, 2024) and leading to mental exhaustion (Mehta, 2025). Distraction, exhaustion, and compulsive engagement are the outcomes. Instead of stealing the user experience, ethical marketers should use neuroscience to enhance it. Knowing how people think and using that knowledge against them are at opposite ends of the ethical spectrum. The goals of ethical neuromarketing are transparency, value, and clarity.

8. Practical Neuromarketing for Engagement

Making your digital strategy brain-friendly doesn’t require a background in neuroscience. Here are some useful strategies for putting these realisations into practice:

- Encourage curiosity: Make use of captivating headlines that convey genuine value (Breda, 2022).

- Less complex design: Cut down on pointless options to save the user’s mental energy (Paletz et al., 2023).

- Try to evoke emotion: Make use of narratives and pictures that evoke strong feelings in people.

- Create expectations in an ethical manner: Give countdowns and surprises genuine value.

- Establish trustworthy feedback loops: To boost participation, give the mind the “you did it” confirmation by using brief animations or encouraging phrases (Abbas et al., 2021).

- Show consideration: Don’t overburden users with pop-ups, auto-play videos, or phoney urgency.

Conclusion

A mouse click is a tiny choice with biological, emotional, and habitual underpinnings. It is not arbitrary; rather, it is motivated by a brain structure that has evolved through evolution and senses reward, relevance, and anticipation.

Digital marketers can turn intuition into strategy by comprehending these processes. The objective is meaningful engagement, not just more clicks; it’s about offering experiences that value human involvement and foster enduring trust. You can communicate your point most effectively if you have a thorough understanding of the human brain.

References

Abbas, M.J., Khalil, L.S., Haikal, A., Dash, M.E., Dongmo, G. and Okoroha, K.R., 2021. Eliciting emotion and action increases social media engagement: an analysis of influential orthopaedic surgeons. Arthroscopy, sports medicine, and rehabilitation, 3(5), pp.e1301-e1308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmr.2021.05.011

Barker, L., 2024. How to Build Occipital Lobes. In How to Build a Human Brain (pp. 165-208). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-55297-7_5

Breda, C., 2022. The role of storytelling in emotional provocation to increase Instagram engagement and the implications on the circulation of information. https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/218005

Chester, D. and Riva, P., 2016. Brain mechanisms to regulate negative reactions to social exclusion. In Social exclusion: Psychological approaches to understanding and reducing its impact (pp. 251-273). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-33033-4_12

Costa, K.M. and Schoenbaum, G., 2022. Dopamine. Current Biology, 32(15), pp.R817-R824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.060

Ensuncho Hoyos, C.F., 2023. Heuristic shortcuts in policy decisions. Entramado, 19(1), pp.247-258. https://doi.org/10.18041/1900-3803/entramado.1.8730

Li, Z., Yan, C., Xie, W.Z., Li, K., Zeng, Y.W., Jin, Z., Cheung, E.F. and Chan, R.C., 2015. Anticipatory pleasure predicts effective connectivity in the mesolimbic system. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 9, p.217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00217

Lindström, B., Bellander, M., Schultner, D.T., Chang, A., Tobler, P.N. and Amodio, D.M., 2021. A computational reward learning account of social media engagement. Nature communications, 12(1), p.1311. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-19607-x

Mehta, K.C., 2025. ‘The World on Our Screens: Protecting the Mind in an Age of Relentless News’, FSB Focus, 10 October. Available at: https://fsb.ac.uk/the-world-on-our-screens-protecting-the-mind-in-an-age-of-relentless-news-on-world-mental-health-day-2025/

Paletz, S.B., Johns, M.A., Murauskaite, E.E., Golonka, E.M., Pandža, N.B., Rytting, C.A., Buntain, C. and Ellis, D., 2023. Emotional content and sharing on Facebook: A theory cage match. Science Advances, 9(39), eade9231. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade9231

Razhankova, I., 2025. ‘Unlocking Learning Barriers: The Hidden Effects of Trauma’, FSB Focus, 25 September. Available at: https://fsb.ac.uk/unlocking-learning-barriers-the-hidden-effects-of-trauma/

Soisoonthorn, T. and Unger, H., 2025. The Human Brain. In A Brain-Inspired Approach to Natural Language Processing (pp. 1-30). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-032-00014-9_1

Youvan, D.C., 2024. Digital Pavlov: How Electronics Condition Human Behavior in the Age of Infinite Rewards. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12787.03369

We hope you enjoyed reading our blog. Join our vibrant academic community and explore endless opportunities for growth and learning at www.fsb.ac.uk/courses or via admissions@fairfield.ac. Discover your path at FSB and embark on a transformative educational journey today.