By Iliana Razhankova, Academic Support Tutor, FSB Croydon.

Higher education is often seen as a time of opportunity, growth, and independence. But for many students, it is also a period shadowed by hidden struggles with trauma, mental health, and emotional wellbeing. While higher education providers are celebrated as spaces for learning and transformation, they are also places where past and present traumas can quietly shape the student experience.

What Do We Mean by Trauma?

To understand how trauma affects higher education, it is important to define what trauma is and how it manifests. Trauma refers to the long-lasting negative impact that deeply distressing experiences can have on a person’s emotions, behaviour, and overall functioning. Such experiences often involve overwhelming feelings of fear, helplessness, confusion, or dissociation, disrupting an individual’s sense of safety and stability (American Psychological Association, 2018).

Trauma can stem from many sources: abuse, neglect, family difficulties such as parental separation, substance misuse, incarceration, or mental health struggles (NHS, 2021; CAMHS, 2023). These adverse experiences are not left behind when students start their degrees; they travel with them, shaping academic journeys in visible and invisible ways (Campbell et al., 2022).

Trauma in Higher Education: A Widespread Reality

Trauma is highly prevalent among higher education students. In the UK, more than half of students report experiencing at least one adverse childhood event before arriving at campus, with many encountering multiple forms of trauma (Hamilton et al., 2024). A cross-sectional survey of 452 UK higher education students found that approximately 76% had experienced at least one traumatic event, with sexual violence and relationship abuse particularly common (Allen et al., 2024). In response to these widespread challenges, the UK government has invested in targeted mental health support for students, including funding dedicated platforms like Student Space for one-to-one support, promoting the University Mental Health Charter Programme, and improving partnerships between higher education institutions and NHS mental health services to better address student needs (GOV.UK, 2024).

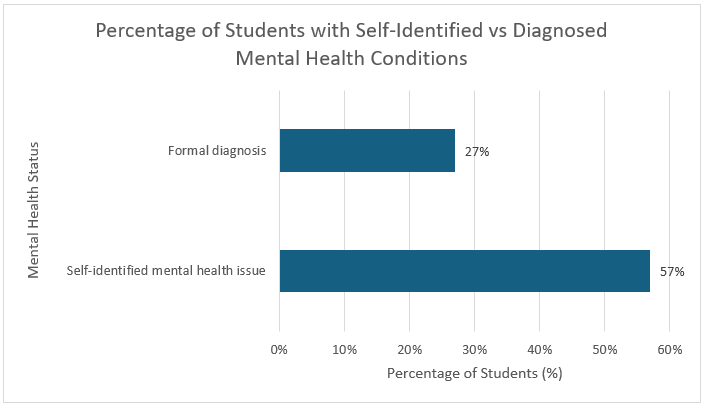

These traumatic experiences are closely linked to broader concerns about student mental health. Surveys consistently reveal high levels of distress, often unrecognised by institutions. For example, a 2022 survey by the charity Student Minds found that 57% of students self-identified as having a mental health issue, while 27% reported a formal diagnosis (Lewis & Stiebahl, 2025; see Figure 1). For many students, these difficulties are inseparable from their trauma histories. Early exposure to abuse, neglect, family conflict, or violence can increase vulnerability to anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Students carrying these burdens may struggle to form social connections, stay engaged academically, or seek support with confidence (Davies et al., 2022).

Figure 1 Percentage of higher education students who reported experiencing a mental health issue versus those who reported a formal diagnosis. Data sourced from a 2022 Student Minds survey (as cited in Lewis & Stiebahl, 2025).

It is also important to recognise that trauma is not solely an individual challenge but a global public health concern. Exposure to trauma carries substantial costs for both individuals and society, with consequences that can affect personal wellbeing, family life, communities, and institutions (Magruder et al., 2017). Within higher education, this perspective highlights that student trauma cannot be viewed in isolation: it affects not only individual learners but also the broader higher education environment, influencing academic outcomes, demand for support services, and campus culture. The consequences for students can be profound. Some experience declining academic performance, social withdrawal, or even leave the degree before completing their studies.

How Trauma Shapes the Student Experience

Trauma doesn’t affect every student in the same way. Some adjust well or even thrive, demonstrating resilience and adaptability, particularly when supported by strong social networks (Allen et al., 2024; Campbell et al., 2022). However, many students face significant barriers that hinder both their learning and wellbeing.

Research shows that trauma is linked to:

- Poor mental health – higher levels of distress, loneliness, and PTSD symptoms (Frazie et al., 2009; Allen et al., 2024).

- Difficulties with adjustment – struggles to build friendships, establish trust, or feel a sense of belonging (Banyard & Cantor, 2004).

- Academic challenges – lower persistence, disengagement from studies, and struggles with focus (Hamilton et al., 2024; Campbell et al., 2022).

- Hidden struggles – many students appear outwardly successful but wrestle privately with emotional pain (Allen et al., 2024).

Importantly, the impact of trauma may not be visible right away. Banyard and Cantor (2004) found that while trauma survivors often seem to adjust similarly to their peers in the early weeks of their degree course, the challenges often surface later, sometimes when academic pressure or isolation increases.

What Lecturers Can Try: Helping Students Feel Safer and More Supported

Creating trauma-informed classrooms requires intentional strategies that support student well-being and academic engagement. Research indicates that trauma-informed pedagogy can significantly enhance students’ sense of safety, participation, and academic success (Wells, 2023; Henshaw, 2022; Harrison et al., 2023). Key strategies include:

Establishing safety and structure – Predictable routines, clear communication, and safe spaces for discussion help students feel secure and ready to learn. According to Wells (2023), classrooms that are structured and welcoming enable students to participate without fear of judgment.

Providing flexible participation options – Offering multiple ways for students to engage (e.g., discussions, written assignments, or online forums) accommodates different learning styles and emotional needs. Harrison et al. (2023) found that flexibility helps students manage stress while remaining academically involved.

Encouraging regular check-ins and open communication – Using short “temperature checks” or anonymous feedback surveys allows educators to gauge student well-being and adjust support accordingly. Henshaw (2022) highlights that consistent, open dialogue between lecturers and students builds trust and enables timely intervention for those experiencing trauma.

Integrating mindfulness and well-being practices – Incorporating brief breathing exercises, guided reflections, or relaxation breaks can help students regulate emotions and reduce stress. Harrison et al. (2023) report that such practices improve focus, emotional control, and academic performance.

Fostering collaborative learning environments – Group projects and peer collaboration promote connection, reduce isolation, and enhance engagement. According to Henshaw (2022), social support within learning communities strengthens resilience and encourages active participation.

By adopting these strategies, lecturers and higher education institutions can create inclusive learning environments that acknowledge trauma, promote psychological safety, and empower students to thrive both academically and personally.

What Students Can Try: Ideas That Might Make a Difference

Research indicates that students who implement structured coping strategies, maintain supportive social connections, and utilise available resources are more effective at managing the challenges of higher education life while also building resilience (Straup et al., 2024; Perry and Cuellar, 2022; Oehme et al., 2019). The following strategies are designed to help students manage trauma, maintain their mental health, and thrive in the higher education environment.

Self-care routines – Maintaining regular sleep schedules, exercising, eating a balanced diet, and practising mindfulness or relaxation techniques can help strengthen resilience and regulate emotions. For example, a student might schedule a consistent bedtime, incorporate short workouts between classes, or dedicate 10 minutes daily to practising meditation or deep breathing. These habits help the body and mind recover from stress and reduce the intensity of trauma-related emotional responses (Straup et al., 2024; Oehme et al., 2019).

Time management and boundaries – Using planners or digital tools, setting realistic academic and personal goals, and avoiding overcommitting can reduce stress and prevent burnout. Students might break assignments into smaller tasks, set reminders for self-care breaks, or politely decline extra responsibilities that could overwhelm them. Establishing boundaries ensures that students can prioritise their well-being while meeting academic expectations (Straup et al., 2024).

Peer support networks – Participating in study groups or workshops organised by academic support services can help reduce feelings of isolation and foster a sense of belonging. Students can connect with peers through collaborative learning sessions, which provide emotional support, encouragement, and practical strategies to cope with academic challenges and stressful situations (Perry and Cuellar, 2022; Oehme et al., 2019).

Use of campus services – Proactively seeking help from mental health counsellors, academic advisors, or disability services can provide structured support for trauma-related challenges. For instance, a student experiencing anxiety or flashbacks could schedule regular sessions with a counsellor or request accommodations for exams. Accessing these services allows students to receive professional guidance and reduces the burden of managing trauma alone (Straup et al., 2024; Oehme et al., 2019).

Grounding and coping techniques – Practising breathing exercises, journaling, mindfulness, or sensory strategies can help students manage stress during lectures, exams, or emotionally triggering situations. For example, students might take a few deep breaths before presentations, write down their thoughts after a stressful class, or use sensory tools like stress balls to stay grounded. These techniques help students stay present and prevent trauma-related symptoms from interfering with academic performance (Perry & Cuellar, 2022).

Trauma-focused self-help interventions – Guided exercises, psychoeducation, or structured self-help programs provide a safe, structured way for students to process trauma. Research shows that these interventions can reduce PTSD, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, allowing students to regain control over their emotions. For example, a student might follow a guided journaling program or online module that teaches coping strategies and helps them work through distressing experiences in manageable steps (Siddaway et al., 2022).

Key Takeaways for Students and FSB Lecturers

Understanding and addressing trauma in the higher education context is essential for both student well-being and academic success. By implementing trauma-informed strategies, lecturers can create structured, flexible, and supportive learning environments. Meanwhile, students can utilise self-care routines, effective time management, campus resources, and coping techniques to navigate challenges and build resilience. Recognising the often-hidden impact of trauma and equipping students with practical tools empowers them to participate more fully in their education, sustain their mental health, and realise their potential. To ensure this support is systemic and sustainable, higher education institutions must embed trauma-informed principles not only into pedagogical practices but also into institutional policies and support systems. In doing so, higher education can become a space not only for learning but also for healing, equity, and transformative growth.

Reference List:

Allen, S. F., Thursby, S., Elkwood, L., and Carthy, N. L. (2024) ‘A latent profile analysis of psychosocial factors and trauma exposure in U.K. students and their association with mental health and academic persistence’, Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice and policy [Preprint]. doi:10.1037/tra0001788

American Psychological Association (2018) Trauma. APA Dictionary of Psychology. [online] Available at: https://dictionary.apa.org/trauma [Accessed: 28 Aug. 2025].

Banyard, V. L. and Cantor, E. N. (2004) ‘Adjustment to college among trauma survivors: An exploratory study of resilience’, Journal of college student development, 45(2), pp. 207-221. doi:10.1353/csd.2004.0017

CAMHS (2023) Trauma. [online] Oxford Health CAMHS. Available at: https://www.oxfordhealth.nhs.uk/camhs/self-care/trauma/ [Accessed 25 Sep. 2025].

Campbell, F., Blank, L., Cantrell, A., Baxter, S., Blackmore, C., Dixon, J., and Goyder, E. (2022) ‘Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: a systematic review’, BMC public health, 22(1), pp. 1778. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13943-x

Davies, E., Read, J. and Shevlin, M. (2022) ‘Childhood adversities among students at an English University: A latent class analysis’, Journal of trauma & dissociation, 23(1), pp. 79–96. doi:10.1080/15299732.2021.1987373

Frazie, P., Anders, S., Perera, S., Tomich, P., Tennen, H., Park, C. and Tashiro, T. (2009) ‘Traumatic Events Among Undergraduate Students: Prevalence and Associated Symptoms’, Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(3), pp. 450–460. doi:10.1037/a0016412

GOV.UK (2024). How we’re supporting university students with their mental health. [online] Blog.gov.uk. Available at: https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2024/03/how-supporting-university-students-mental-health/ [Accessed 25 Sep. 2025].

Hamilton, J., Welham, A., Morgan, G., and Jones, C. (2024) ‘Exploring the prevalence of childhood adversity among university students in the United Kingdom: A systematic review and meta-analysis’, PloS one, 19(8), p. e0308038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0308038

Harrison, N., Burke, J. and Clarke, I. (2023) ‘Risky teaching: Developing a trauma-informed pedagogy for higher education’, Teaching in Higher Education, 28(1), pp. 180–194. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1786046

Henshaw, L. A. (2022) ‘Building trauma-informed approaches in higher education’, Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), p. 368. doi:10.3390/bs12100368

Lewis, J. and Stiebahl, S. (2025) Student mental health in England: Statistics, policy, and guidance. House of Commons Library, UK Parliament. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8593/ [Accessed: 01 Sep. 2025].

Magruder, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A. and Elmore Borbon, D. L. (2017) ‘Trauma is a public health issue’, European journal of psychotraumatology, 8(1), p. 1375338. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1375338

NHS (2021) Bereavement and traumatic events – Every Mind Matters. [online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/every-mind-matters/lifes-challenges/bereavement-and-traumatic-events/#traumatic-events. [Accesed: 25 Sep. 2025]

Oehme, K., Perko, A., Clark, J., Ray, E. C., Arpan, L. and Bradley, L. (2019) ‘A trauma-informed approach to building college students’ resilience’, Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 16(1), pp. 93-107. doi:10.1080/23761407.2018.1533503

Perry, Y. and Cuellar, M. J. (2022) ‘Coping methods used by college undergraduate and graduate students while experiencing childhood adversities and traumas’, Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 15(2), pp. 451-459. doi:10.1007/s40653-021-00371-z

Siddaway, A. P., Meiser‐Stedman, R., Chester, V., Finn, J., Leary, C. O., Peck, D. and Loveridge, C. (2022) ‘Trauma‐focused guided self‐help interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials’, Depression and anxiety, 39(10-11), pp. 675-685. doi:10.1002/da.23272

Straup, M. L., Prothro, K., Sweatt, A., Shamji, J. F. and Jenkins, S. R. (2024) ‘Coping strategies and trauma-related distress of college students during Covid-19’, Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 26(3), pp. 882-899. doi:10.1177/15210251221126162

Wells, T. (2023) ‘Creating trauma-informed higher education classrooms’, Journal of Effective Teaching in Higher Education, 6(1), pp. 97-111. doi:10.36021/jethe.v6i1.336

We hope you enjoyed reading our blog. Join our vibrant academic community and explore endless opportunities for growth and learning at www.fsb.ac.uk/courses or via admissions@fairfield.ac. Discover your path at FSB and embark on a transformative educational journey today.